Last Updated: 11-2020

Definitions and Sources

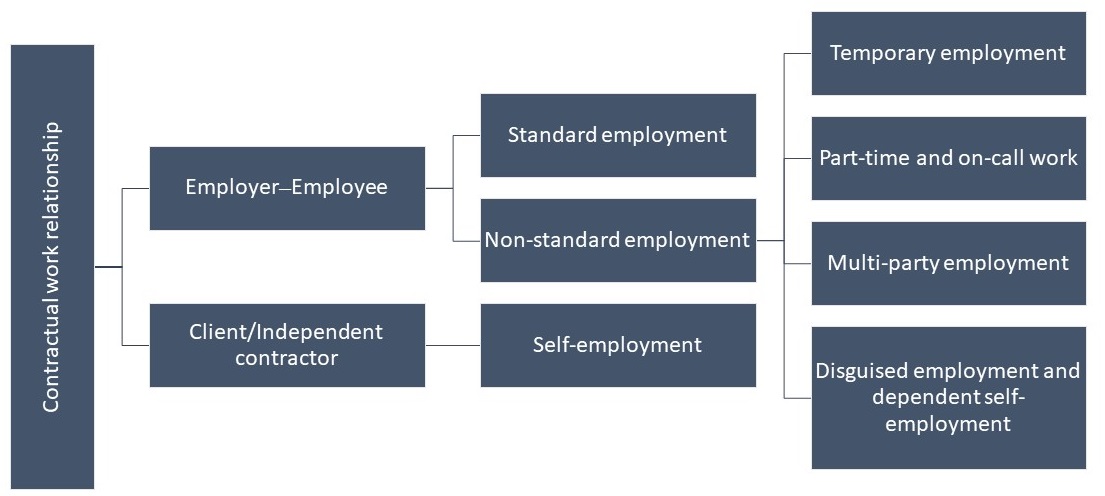

Work in Canada is classified into three broad categories based on whether an employer–employee relationship exists and, if so, the nature of that relationship (see Box 1). These categories, referred to as “work arrangements,” include 1) standard (or traditional) employment, 2) non-standard employment, and 3) self-employment (see Figure 1).

Identifying the status of a worker (i.e., an employee or independent contractor) and the particular work arrangement in which they are engaged is important for two primary reasons. First, it determines how an individual is taxed (Income Tax Act). Second, a worker’s status directly affects their entitlement to employment insurance (EI) benefits under the Employment Insurance Act. Employees (i.e., workers engaged in an employer–employee relationship), for example, in both the federal and provincial labour systems receive protections under labour standards and health and safety legislation that are not conferred to independent contractors (i.e., workers who are self-employed).

Due to factors such as globalization and technological advancement, which continue to drive changes to the world of work, new forms of employment are emerging (International Labour Organization, 2016), and as the share of workers who engage in non-standard types of employment increases, it is important to call attention to and clarify the differences between these three types of work arrangements.

Box 1: Defining an employment relationship

“Employment” describes a contractual relationship in which one individual, called an employee, agrees to do work in exchange for compensation according to the direction of another person, called an employer. This relationship, called an employer–employee relationship, is entered into when a person is hired to be an employee (Employment and Social Development Canada, Labour Standards Interpretations, Policies and Guidelines).

Another type of contract that can exist occurs when a person, called an independent contractor or service provider, commits to carrying out work or providing a service for a fee to another person, called a client. This type of contractual relationship is not referred to as employment and differs from an employment contract, which establishes an employer–employee relationship, in that the contractor is free to choose the means of performing the contract and no relationship of subordination exists (Employment and Social Development Canada, Labour Standards Interpretations, Policies and Guidelines).

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) publishes a guide to help both payers (or employers) and workers decide a worker’s employment status. In addition, the Supreme Court of Canada, in Ontario Ltd. v. Sagaz Industries (2001), outlines several conditions for determining if a worker is an employee (i.e., engaged in an employer–employee relationship) or an independent contractor (i.e., self-employed). The characteristics of employees and independent contractors are summarized in Table 1.

Nevertheless, contractual work relationships can be complex, and while the goal of this entry is to explain the different types of relationships that exist, it is not meant to replace legal counsel.

Figure 1: Types of contractual work relationships

Table 1. Contrasting characteristics of employees and independent contractors.

| Employee | Independent Contractor |

| Works exclusively for the payer | May work for other payers |

| Payer provides tools | Worker provides tools |

| Payer controls duties, whether that control is used or not | Worker decides how the task is completed |

| Payer sets working hours | Sets own working hours |

| Worker must perform services | May hire someone to complete the job |

| Provision of pension, group benefits | Not allowed to participate in payers’ benefits plans |

| Worker is paid vacation pay | No vacation pay, and no restrictions on hours of work or time off |

| Payer pays expenses | Worker pays own expenses |

| Paid salary or hourly wage | Worker is paid by the job on a predetermined basis |

| Reports to payer’s workplace on regular basis | Submits invoice to payer for payment |

| Worker may accept or reject work |

Note: Adapted from Employment and Social Development Canada, Interpretations, Policies and Guidelines (IPGs).

Standard and Non-Standard Employment

“Standard employment” describes an employment relationship between one employer and one employee that is both full-time and permanent.

“Non-standard employment” describes any employment (i.e., employer–employee relationship) that deviates from standard employment (see Box 1). Individuals engaged in non-standard employment are usually not entitled to the employee protections as enumerated in the federal and provincial labour standards.

Four types of non-standard employment are widely accepted to exist:1

- Temporary employment refers to arrangements where workers are employed only for a predetermined period. It includes fixed-term contracts, project- or task-based contracts, seasonal and casual work.

- In Canada, part-time work usually describes any employed person working fewer than 30 hours per week at their main job. On-call work usually refers to working arrangements that involve either very short hours or no predictable fixed hours, and where the employer has no obligation to provide a set number of hours of work.

- Multi-party employment (or “triangular employment”) describes working arrangements whereby workers are not directly employed by the company to which they provide their services but rather by a third-party agency. Human Resource (HR) consultants, for example, may engage in a multi-party employment arrangement since it is common for firms to outsource their human resource functions. The firm contracts with a professional HR company to perform personnel-related duties. The HR company then assigns one or more consultants to the firm. These consultants, however, are not employed by the firm but by the HR company. In this case, there is a commercial contract that binds the firm and the HR company, but there is no employment relationship between the HR consultant and the firm.

- Disguised employment and dependent self-employment refer to employment arrangements whose appearance is different from the underlying reality. These workers are often misclassified as independent contractors (i.e., self-employed) or multi-party workers. They will typically have employment characteristics that lie between those of employees and independent contractors.

-

- Disguised employment (also referred to as “false self-employment”) describes an employment arrangement masked as a civil law relationship. It occurs when the work performed is governed by a service contract or other civil agreement rather than an employment contract. Doing so prevents the person conducting the work from being classified as an employee, thus excluding them from certain legal protections and/or employment insurance. This type of arrangement can sometimes occur when a company works with an independent contractor but the contractor is expected to behave as an employee. It is more common among labour-intensive industries, such as construction and transportation.

- Dependent self-employment describes an employment arrangement where the worker is classified as self-employed — and thus not entitled to certain legal employment protections — but whose income is dependent on one main firm or client. Maintenance contracts for hotel facilities, such as electricians and plumbers, are often examples of dependent self-employment. These workers are self-employed (i.e., independent contractors), using their own tools and organizing their tasks autonomously, but earning most of their income from the hotel.

Non-Standard Employment, Precarious Work and the Gig Economy

The term “non-standard employment” is often conflated with the labour market concepts of “precarity” (also known as “precarious work”) and “gig work.” Although the three concepts are often used interchangeably, they are distinct. As described above, non-standard employment refers to any one of several types of employer–employee relationships deviating from traditional employment.

Precarity is a more general concept concerning the wellbeing and/or fairness of one’s work arrangement. It is often thought of in terms of wages earned, benefits provided (or not provided) and other working conditions that cut across employment types (i.e., standard and non-standard employees could be engaged in either precarious or non-precarious work). See Box 2 for the definition of precarious work.

Because there is no universally agreed upon definition of gig work, the relationship between non-standard employment and gig work (and between precarity and gig work) is more complicated so they should be treated as distinct concepts. Future research will explore how best to consider “gig work” within this framework based on a review of international literature and best practices.

Box 2: Defining Precarious Work

“Precarious work” (noun: “precarity”; adjective: “precariousness”) generally refers to work where the employee, rather than the employer, bears the risk of the job. While there is no official definition for precarious work in Canada, the International Labour Organization (ILO) defines precariousness by “risky” job attributes such as low pay (i.e., earnings at or below the poverty line), uncertain continuity of employment or high risk of job loss, little or no choice about working conditions (e.g., schedule or wages), and few to no job protections guaranteed by law or through collective agreements (e.g., lack of job benefits, and social, health and safety, and other protections typically associated with standard employment).

Sources: (ILO, 2016). Non-Standard employment around the world: Understanding challenges, shaping prospects.

Data Sources

Most collection of non-standard employment data in Canada began in 1997 (Crane, 2016). As of 2017, non-standard employment made up 26% of total employment in Canada (Statistics Canada).

Labour Force Survey (LFS)

Every month, the Labour Force Survey collects data from approximately 53,000 households. It provides estimates on the labour force status, wages and demographic characteristics of the civilian non-institutional population 15 years of age and older. The LFS collects data on non-standard employment (NSE) and workers. It distinguishes between part-time and full-time workers, seasonal and non-seasonal workers (i.e., temporary), and those working for fewer than 30 hours per week.

General Social Survey (GSS)

Annually, the General Social Survey (GSS) gathers household data on social trends to monitor changes in the living conditions and well-being of Canadians over time, and to provide information on specific social policies. It is organized by theme (e.g., caregiving, families, time use, victimization, etc.), with each theme repeated every five years or so. Since 2014, survey results have been linked to tax files.

Two GSS surveys — cycles 4 and 9 collected in 1989 and 1994 — covered content related to education, work and retirement. These cycles contained questions like those in the LFS on the temporary nature of jobs. Part-time work and part-year work was defined as the main job typically lasting nine months or less per year. This theme, however, is not included in the current GSS.

Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID)

The Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) contains questions on labour market participation over time. It follows a panel of individuals over a six-year period, collecting detailed information on family structure, personal and family income, educational attainment, disability, immigration status and a wide range of other socioeconomic characteristics. It distinguishes among three groups of non-standard workers: 1) those self-employed (with and without paid help), 2) employees with permanent part-time jobs, and 3) temporary employees who work either full or part time. SLID was replaced by the Canadian Income Survey (CIS) in 2012.

Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (EICS)

The main objective of Statistics Canada’s cross-sectional Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (EICS) is to provides a picture of who does or does not have access to employment insurance benefits among the jobless and underemployed. EICS data tracks the number of workers in NSE prior to unemployment. The survey is administered to a sub-sample of LFS respondents four times a year in April–May, July–August, November–December and January–February. The target population for this survey is the unemployed and others who, given their recent status in the labour market, could potentially be eligible for employment insurance.

Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations (CSCE)

The Bank of Canada’s quarterly Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations (CSCE) primarily measures household/consumer views of inflation, the labour market and household finances. Data is organized by age, geography, income and education. A key benefit of the CSCE is that one-off questions can be introduced to help deepen understanding of recent economic developments. In 2018, new questions identified workers who participate in informal “gig” work and their reasons for engaging in such jobs. CSCE data can be used to track informal work activities.

Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database (CEEDD)

Statistics Canada’s annual Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database (CEEDD) includes several linked longitudinal administrative data sets of employers and employees grouped by unique individual and business identifiers. The currently available data covers 2001 to 2017 and includes individual and business tax files such as T1 personal, family and business declaration files, the T2 files (corporate tax return and owner files), and T4 supplementary files. Tax files include all sources of income for both individuals and businesses and thus can be used to track both standard and non-standard employment.

Because CEEDD is linked to several administrative datasets, including the longitudinal immigration database (IMDB), it can be used to explore many issues including local labour market information trends such as hiring rates, separation rates, layoff rates, aggregate turnover rates, firm growth and dynamics, and labour productivity.

Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS)

Statistics Canada’s cross-sectional Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS), conducted occasionally, collects information about the impact of digital technologies on the lives of Canadians. Data relates to online work, the use of online government services, social networking websites or apps, smartphones, digital skills, e-commerce, and security, privacy and trust. CIUS data can be used to observe a subset of NSE related to online work (i.e., gig work).

In 2005, the CIUS replaced its predecessor the Household Internet Use Survey (HIUS), first conducted in 1997 to measure household Internet penetration in Canada. The most recent 2018 estimates were published in October 2019; the prior survey was conducted in 2012. The 2018 questionnaire was redesigned to include questions about a wide range of activities including online work. Respondents were asked if they used the Internet or peer-to-peer apps to earn income and if it was their primary source of income.

Survey of Work Arrangements (SWA)

Statistics Canada’s Survey of Work Arrangements (SWA) supplemented the LFS in 1991 and 1995, collecting information on work schedules, hours of work, flexible hours, home-based work, and employee benefits and wages. It identified those who worked different hours each day, job shared (i.e., worked fewer than 30 hours per week due to sharing the job with someone else), the number of hours worked from home, whether the job was permanent, if they were covered by union contract or collective agreement, and whether they were entitled to various benefits.

Data Access

All these different sources of data can be accessed through the channels presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Statistics Canada data access

| Data Tables | Customized Products | Public Use Microdata File (PUMF) | Real Time Remote Access (RTRA) | Research Data Centre (RDC) | Canadian Centre for Data Development and Economic Research (CDER) | |

| Labour Force Survey (LFS) | Several tabulations available | Several tabulations available per confidentiality release criteria | Available | Available | Available | NA |

| General Social Survey (GSS) | Data before 2000 not available (Cycle 14) | Several tabulations available per confidentiality release criteria | Data before 2006 not available (Cycle 20) | Data before 2002 not available (Cycle 16) | Available | NA |

| Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) | Several tabulations available | Several tabulations available per confidentiality release criteria | Available | Available | Available | NA |

| Employment Insurance Coverage Survey (EICS) | NA | Several tabulations available per confidentiality release criteria | Available | Available | Available | NA |

| Canadian Survey of Consumer Expectations

(CSCE) |

NA | Available via the Bank of Canada website | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics

Database (CEEDD) |

NA | Customized tabulations available via Statistics Canada’s Analytical Studies Branch | NA | NA | NA | Available |

| Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS) | Several tabulations available | NA | Available | Available | Available | NA |

| Survey of Work Arrangements (SWA) | 1995 tabulation available | Several tabulations available per confidentiality release criteria | Available | NA | Available | NA |

Applications

As previously discussed, the work arrangement under which a worker is classified has important implications for taxation and employment insurance eligibility. In addition, information on standard and non-standard employment is used by a variety of stakeholders for other purposes as well.

Governments and policy makers

Federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal governments and policy makers use non-standard employment (NSE) information to inform data-driven policy development targeting these workers. It is also used to evaluate the performance of government programs and policies on the economic and social well-being of NSE workers.

Researchers and other labour market professionals

Researchers use NSE information to analyze economic and labour market trends. It can also be used to identify the sociodemographic characteristics, occupations, industry, geography and immigration status of NSE workers.

End Notes

- The ILO is working to expand the definitions of non-standard employment to include crowdwork, gig work and remote work. These terms will be elaborated on in future Insights and/or WorkWords entries as they become available.