Not Your Average “Future of Work” Event

The world of work is changing. This is evident by the number of new job opportunities stemming from technological advancement, the restructuring/disruption of jobs, and the burgeoning field of predicting future job gains and losses. Since I am an economist at LMIC and a board member of the Ottawa Economics Association (OEA), these emerging and uncertain trends are of particular interest to me. So, I was thrilled to learn that Georg Fischer, Senior Research Associate at the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, was in Ottawa last month to present at a joint OEA/Canadian Association of Business Economics (CABE) networking event. Mr. Fischer was to be interviewed by CABE President, Armine Yalnizyan. Given Mr. Fischer’s extensive experience in international social policy and Ms. Yalnizyan’s role as Economic Policy Advisor to the Deputy Minister at Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), I knew this was not going to be your average “Future of Work” event.

Through the contributions of my colleagues and myself to LMIC’s Future of Work Annotated Bibliography, I have seen a frequent focus on quantifying the risk that various occupations have to being replaced by machines. I expected Mr. Fischer to focus on the same. Yet, to my surprise, he instead discussed another important risk in the future of work: the decreasing quality of jobs.

How to Define Job Quality?

According to Fischer, the main labour market risk in the 21st century is not job loss per se, but the declining quality of jobs. The primary driver, he argues, is increasing “job polarization”: a decreasing share of middle-income jobs and a rising share of low- and high-income jobs. Although his comments focused on the European Union (EU), job polarization happens in the Canadian context as well (see Green & Sand, 2013).

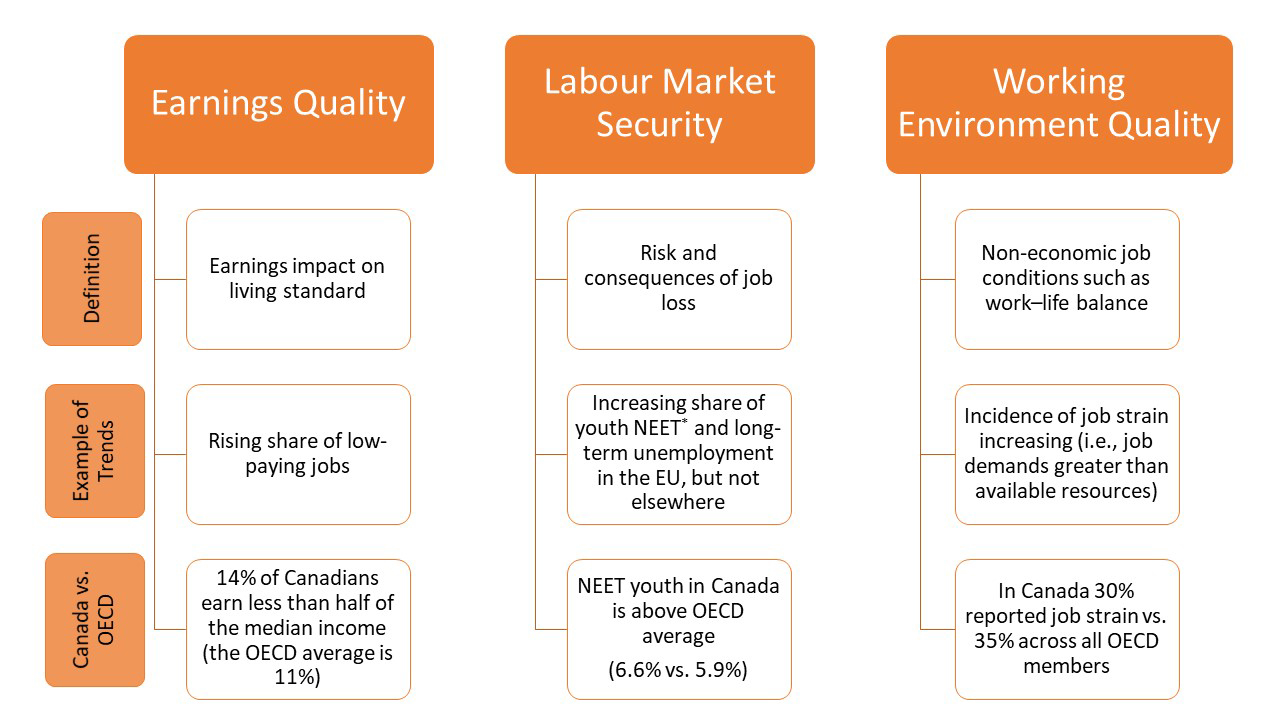

In 2016, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) introduced a framework to measure and compare the quality of jobs across countries. The framework has three main dimensions: earnings quality, labour market security, and quality of the working environment. The chart below provides an overview of these dimensions, as well as their recent trends and how Canada stacks up against other OECD economies.

Sources: Georg Fischer; OECD

* NEET stands for “not in employment, education, or training.”

What Can Be Done?

According to both Mr. Fischer and the OECD, improving job quality will create healthier, more productive workers, which in turn can improve output and overall economic growth. Improving job quality will require smart policy making. Fischer argues that inclusive social policies can act as automatic stabilizers and help reduce the negative impact of falling job quality. This includes facilitating access to affordable and useful skills development and training, improvements to Employment Insurance (EI) programs, and universal basic income. By reforming social protection policies and labour market laws, governments can ensure that lower-paid workers have a standard of living that fosters creativity and innovation, and enables them to keep up with the changing world of work.

Way Forward — Don’t Play Catch Up, Be Proactive

If we are proactive about the future of work — that is, putting in place a strategy that prioritizes social inclusion — then we can take advantage of the many opportunities offered by new technology.

For more background information on the future of work, and how it relates to the Canadian economy, be sure to check out LMIC’s Future of Work Annotated Bibliography.

Sign up for our newsletter to stay up to date with our efforts to help Canadians navigate the changing world of work.

Bolanle Alake-Apata is an Economist with LMIC. Her work currently focuses on conducting research on labour market information for recent immigrants and students.