Table of Contents

Key Findings

- Past assessments of Canadian labour market information (LMI) have been instrumental in identifying gaps and guiding LMIC’s priorities

- Considerable progress has been made in improving labour market information in Canada, but a number of important gaps persist. In collaboration with its stakeholders, LMIC will make efforts to address these, notably the following:

- Improving our collective understanding of the labour market information needs of Canadians

- Assessing and testing a range of methods to generate timely, local, granular labour market nformation

- Providing insights - including best practices, information, and methodological considerations - to support initiatives related to skills, labour shortages, and skills mismatches

- Using linked administrative data to enhance knowledge of the factors underlying the labour market outcomes of Canadians

Introduction

Canada’s labour market and workplaces are evolving at an unprecedented pace. Drivers such as technology and business model innovations, an aging population, evolving global trading patterns, and climate change create uncertainty around employment, job quality, skill requirements, and the ability to form, attract, and retain talent. In this context, improving the timeliness, relevance, and reliability of labour market information (LMI) is essential to helping Canadians navigate the changing world of work.

A first step to improving the LMI system in Canada is to recognize the considerable efforts that have been undertaken in the past decade to identify - and make progress in closing - labour market information gaps. The aims of this inaugural edition of LMI Insights are threefold: (i) review and assess previously identified LMI challenges; (ii) identify key persistent LMI gaps; and, (iii) highlight where LMIC, in collaboration with its stakeholders, can contribute to improving LMI in Canada.

Considerable progress, but gaps remain

In 2009, to increase coordination and to share LMI knowledge, the Forum of Labour Market Ministers - representing the federal, provincial, and territorial labour ministries - established the Advisory Panel on Labour Market Information (APLMI) to provide a thorough assessment of how to improve Canada’s LMI system. Since then, several other LMI assessments have been conducted, mainly by APLMI chair Don Drummond, to chart progress and identify persistent gaps (see Box 1).

In examining these reports, we found that four main themes of LMI gaps persist:

- Information is not sufficiently tailored to users’ needs: LMI is not easily accessible to individual Canadians and is rarely provided in a format that lends itself to informed decision-making. This situation is exacerbated given the wide diversity of end-users and use-cases.

- Missing local granular data: The lack of sufficient local, granular data persists. This has been consistently identified as a shortcoming in being able to help Canadians make informed decisions. Providing this data is essential to improving Canada’s LMI system.

- Confusion regarding labour and skill mismatches: Employers and policy makers have long called for labour market information that provides insight into skills in addition to occupations. However, clarification is needed to better understand how to measure and interpret skills, skills mismatches, and labour shortages.

- Limited insights on labour market outcomes of Canadians: A lack of timely and comparable information and insights on how Canadians - including students, youth, and under-represented groups - perform in the labour market remains a gap in the LMI system.

In the discussion that follows, these four main themes are discussed in more depth, with emphasis on identifying where progress has been made and highlighting ways forward to improve labour market information in each area.

Box 1: Past assessments of the Canadian LMI System

For this edition of LMI Insights, we reviewed a wide range of reports. Most notable among these is the APLMI (2009) report, widely considered the seminal contribution to LMI issues in Canada. Since its publication in 2009, two other reports authored by APLMI’s chair, Don Drummond, have been published (Drummond, 2014; Drummond & Halliwell, 2016). Several other analyses were also assessed as part of this review, including reports from the Canadian Chamber of Commerce (2015), Aon Hewitt (2016), the C.D. Howe Institute (Alexander, 2016), and the Canada West Foundation (Lane & Griffiths, 2017).

Designing LMI for end users

One of the central recommendations of several LMI assessments was the need for a "one-stop shop" or single port of entry for all LMI. In some areas, notably with respect to the consolidation of government-sponsored job posting boards, there has been progress in aligning functionality and, in some cases, merging or collapsing the websites into one. All jurisdictions have also made strides in taking a client-oriented approach to disseminating LMI by offering interactive portals and establishing networks of local intermediaries to enhance dissemination of local labour market information (e.g., Ontario’s Local Employment Planning Councils, Emploi-Quebec’s directions regionals, etc.). Similarly, since 2017, Statistics Canada’s modernization efforts have focused on improving how people and businesses find and use the wealth of information collected by the agency.

However, by its very nature, Canada’s LMI system is highly diffuse, with a wide range of information, users and providers. Such diffusion is exacerbated by rapid technological developments in recent years on how information is consumed (e.g., via smartphones) and shared (e.g., via social media platforms). LMI users are also very diverse, ranging from policymakers at the federal, provincial, regional, and local levels, to employers, workers, students, parents, educators, career practitioners, jobseekers, and, indeed, anyone looking for information to support their decision-making process.

Moreover, various groups - notably women, persons with disabilities, Indigenous peoples, youth, older workers, visible minorities, and recent immigrants - require information relevant to their unique experiences. Some steps toward improving the collection of information in a number of these areas include federal surveys such as the Canadian Survey on Disability, the Aboriginal Peoples Survey,

the First Nations Regional Early Childhood,Education, and Employment Survey,1 and provincial and territorial initiatives (e.g., Northwest Territories’ Community Survey).

This diverse LMI user base translates into an equally varied set of informational needs, not just in terms of content (i.e., what information), but also form (i.e., how the information is accessed). Addressing the needs of these diverse user groups requires that LMI data, insights, and outlooks be disseminated across a variety of platforms with content focused on user needs and creative usability design. A single platform will simply not do the job.

LMIC is taking a three-pronged approach to this challenge: (i) by working with stakeholders to catalog the wide range of existing labour market information; (ii) by seeking to better understand the diverse LMI needs of Canadians; and, (iii) by ensuring that reliable LMI is disseminated through multiple platforms to ensure accessibility and effectiveness.

Success in closing these LMI gaps will require input from Canadians, where the diversity of LMI needs is still not clearly understood. To that end, LMIC is conducting a major public opinion research study to identify how Canadians use LMI and what they find to be lacking in the current system (see Box 2).

Box 2: Public opinion research on labour market information needs and uses

In working toward user-centric LMI for Canadians, LMIC has initiated a public opinion research study. Over 20,000 individuals and organizations are being surveyed to better understand how they make their education, workplace, and career decisions, as well as which information they use, including their assessment - both content and form - of this information. In total, we will survey nine user groups: employed persons, unemployed persons, recent graduates, recent immigrants, persons with disabilities, current college/ university students, parents, employers, and career practitioners. Notably, the survey is designed to produce representative results for each province and differentiate between urban and rural areas across Canada.

Results from these surveys will be made publicly available as raw data and as interactive visualizations on our website. Further, LMIC will work with stakeholders to interpret the empirical results and identify remaining LMI gaps. LMIC will also establish ongoing partnerships with these and other under-represented populations to further investigate specific LMI needs. Ultimately, the research findings will be used to inform actionable recommendations for better LMI dissemination tools and methods.

Improving local granular data

Another common theme in the assessments of Canada’s LMI is the call for more local, granular data to parallel the nature of decisions made by individuals, policy makers, organizations, and others. Making data more "local" typically means access to indicators at the sub-provincial level, including smaller towns and rural areas; "granular" implies access to highly disaggregated LMI data, including for instance information on occupations, industries, workplaces, job quality, and inclusiveness.2

Two crosscutting issues in the contexts of "local" and "granular" are the twin needs to (i) improve the timelessness of the data and (ii) narrow the information gap for under-represented groups for which LMI data of this nature is particularly limited. To improve LMI in this area, recommendations in earlier reports principally focused on establishing new surveys or redesigning existing ones.

Several initiatives are being implemented to generate more local, granular data, notably Statistics Canada’s pilot projects to produce small area estimations from the Labour Force Survey. In addition, several jurisdictions have acquired more local data by purchasing private third-party data or through oversampling on national surveys.3 In other cases, some jurisdictions have implemented their own surveys. While surveys remain an important means of collecting data, however, they remain costly, especially if implemented on a regular basis.

Proposals to leverage new methods of gathering such information in a more cost-effective but equally reliable manner have emerged in recent reports. This includes the use of unstructured data, modelling techniques and administrative dataset linkages (now more widely accessible). Beginning with the 2011 Open Government plan, the federal government, in collaboration with the provinces and territories, has increasingly provided standardized access to administrative data. A prime example is Statistics Canada’s 2011 decision to provide free online access to public-use microfiles. Another example is Employment and Social Development Canada’s move to implement two-way data sharing on clients funded through Labour Market Development and Workforce Development agreements. Yet, while the use of administrative dataset linkages can be cost-effective, they often come with a delay, so are not as timely as traditional surveys.

Moving forward, in partnership with Statistics Canada and other stakeholders, LMIC is exploring the feasibility of these and other approaches to increase the availability of timely, local, granular LMI, especially for those populations where such data is particularly challenging to obtain.

Enhancing our knowledge and understanding of labour shortages and skill mismatches

Concern over labour shortages across Canada has grown among policy makers in recent years. The conversation about labour shortages, however, has steadily moved over the years toward skills and skills mismatch (as seen in the 2016, 2017, and 2018 federal budgets). As workplaces undergo dramatic changes, the lack of relevant, reliable LMI information and insights in this area contributes to the disconnect between the ability of employers to find people with the right skills and for individuals (along with education and training institutions) to know what skills and training to invest in.

In this context, a main recommendation from previous reports, notably Drummond (2016), was to have a clear picture of the skillsets needed for various jobs. Reducing labour imbalances4 requires, among other tools, improved clarity of definitions and measurement of skills and labour shortages as well as easily accessible information about the skills demanded today and expected tomorrow. A number of efforts are underway in this vein. For example, the federal government has announced a future skills initiative, including a Future Skills Council and a Future Skills Centre, an arm’s-length body focused on skills assessment and development, among other things (Box 3).

To support improving LMI in this area, LMIC will assess the data gaps, identify best practices, and provide additional clarity to understand and measure these complex issues. In doing so, LMIC’s goal is to support related initiatives, including the Future Skills Centre, by collaborating on areas of mutual interest and providing the necessary labour market information and insights on these matters.

Box 3: Canada’s Future Skills Initiative

Future Skills was announced in Budget 2017 and reaffirmed in Budget 2018. The aim is to support skills development and measurement in Canada, and to build a highly skilled, resilient workforce. It will pinpoint the skills required by employers now and into the future, explore innovative approaches to skills development, and share information for future investments and programming. Working in collaboration with provinces and territories, the private sector, educational institutions, labour, and not-for-profit organizations, it will include the following elements:

- A Future Skills Council to advise on emerging skills and workforce trends

- A Future Skills Centre, arm’s-length from the government, focused on developing, testing, and rigorously measuring new approaches to skills assessment and development

Source: For more information, visit here.

Improving knowledge of labour market outcomes of Canadians

Considerable investments, financial and otherwise, go into training and educating Canadians through schooling, apprenticeships, and on-the job training to equip them with the necessary skills and qualifications to succeed in their careers and in life. Information about the return on these investments is essential so that policy makers, institutions, and Canadians can make informed decisions. For post-secondary education, Statistic Canada’s National Graduate Survey has been the main tool used to measure graduates’ performance. The timing (every five years) and scope (estimation unavailable at the sub-provincial level), however, hinder its relevance for provincial and territorial jurisdictions, who conduct their own surveys.

Innovative and cost-effective approaches, therefore, are being implemented to improve data availability. Chief among these is the Education and Labour Market Linkage Platform (ELMLP), announced in the 2018 federal budget. By linking post-secondary and apprenticeship information with T1 Family File (T1FF) anonymized tax data, ELMLP tracks students in a wide variety of programs (e.g., universities, colleges, apprenticeships) through graduation and through their subsequent outcomes in the labour market, including annual income.

Along with our key stakeholders, LMIC is working to develop broad, inclusive indicators of labour market outcomes for students to help identify any opportunities for improvement. More broadly, LMIC aims to improve the robustness of data and the analyses of labour market outcomes for Canadians - including students, youth and underrepresented groups - and translating them into actionable information and user-friendly insights.

The way forward

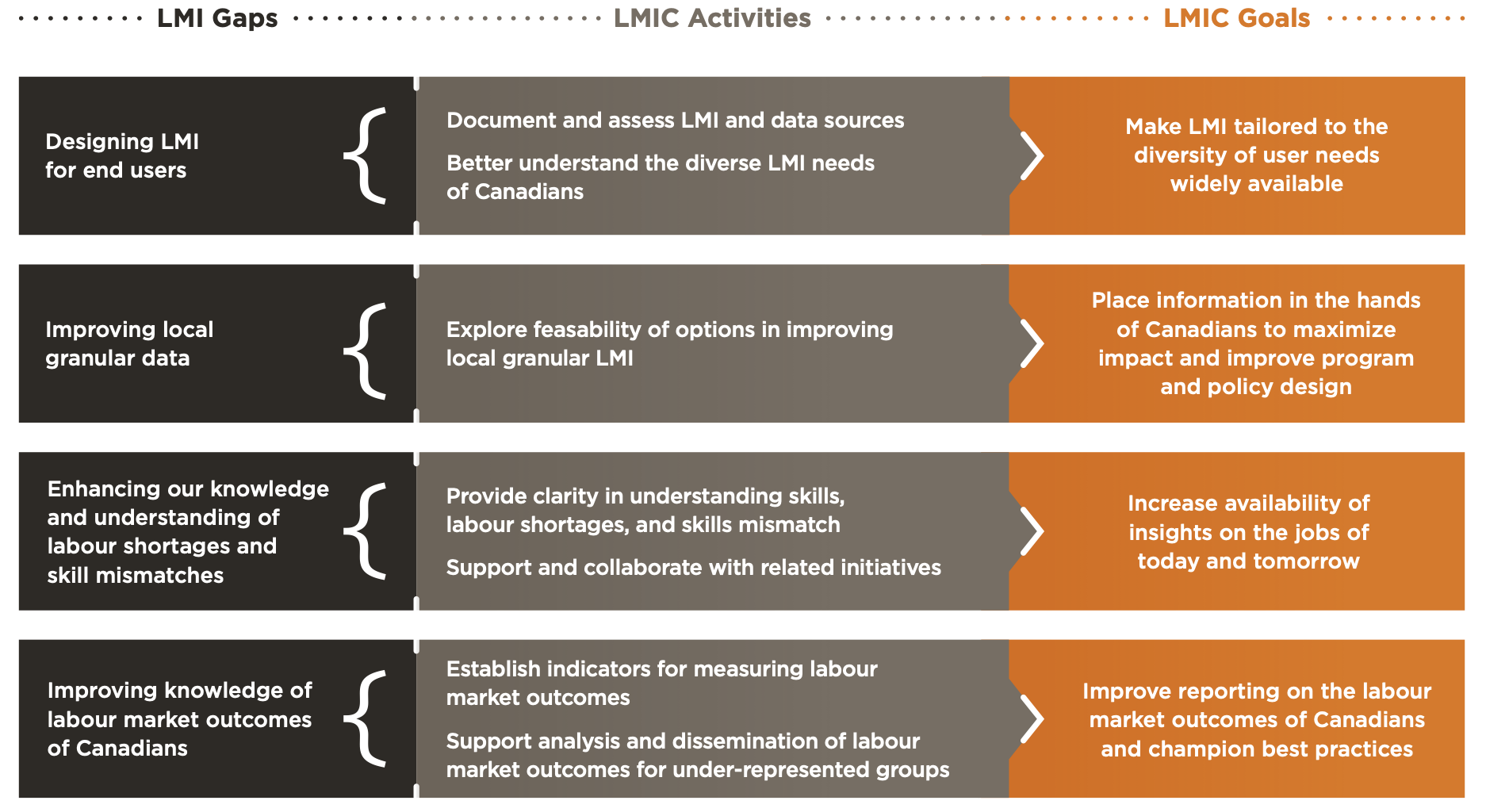

A first step in understanding the prevailing labour market information in Canada was to document and review past reports that assessed the situation. This included assessing the validity of and progress towards key recommendations stemming from these reports, particularly those that align with LMIC’s strategic goals. This inaugural edition of LMI Insights reveals that despite progress in several areas of labour market information, gaps persist in four key areas (see Figure 1). Moving forward, LMIC will work with our stakeholders to assess potential approaches and to develop solutions for closing these gaps, including the respective roles of each stakeholder and of LMIC itself.

Addressing the challenges and opportunities presented by the changing nature of work is no easy task; it requires a range of complementary, mutually reinforcing efforts. In that context, timely, relevant, reliable labour market information is not enough, but it is undeniably essential in our collective efforts to help Canadians succeed.

Figure 1. Closing key LMI gaps: The way forward

This LMI Insight was prepared by Emna Braham of LMIC. We would like to thank LMIC’s partners in federal, provincial and territorial jurisdictions as well as in our National Stakeholder Advisory Panel and Labour Market Information Experts Panel for their comments and suggestions in preparing this LMI Insight. In particular, the team would like to acknowledge the valuable feedback and input of Derrick Barrett, Sandip Basi, Charles Beach, Josée Bégin, Kate Bolton, David Chaundy, Ana Ferrer, Rachel Gaudreau, Debra Hauer, Judith Hayes, Tanveer Islam, Karen Charnow Lior, Steve St-Pierre, David Ticoll and Ruth Wittenburg.

For more information about this LMI Insight or other LMIC activities please contact Emna Braham, Senior Economist at emna.braham@lmic-cimt.ca or Tony Bonen, Director, Research and Analytics tony.bonen@lmic-cimt.ca.

References

Advisory Panel on Labour Market Information (APLMI). (2009). Working together to build a better labour market information system for Canada: Final report. Available here.

Alexander, C. (2016). Job one is jobs: Workers need better policy support and stronger skills. C.D. Howe Institute. Available here.

Aon Hewitt. (2016, March). Developing Canada’s future workforce: A survey of large private-sector employers. Aon Hewitt and Business Council of Canada. Available here.

Canada. (2016). The Budget. Available here.

Canada. (2017). The Budget. Available here.

Canada. (2018). Budget plan. Available here.

Canadian Chamber of Commerce. (2015). How good is Canada’s labour market information? Available here.

Drummond, D. (2014). Wanted: Good Canadian labour market information. IRPP. Available here.

Drummond, D., & Halliwell, C. (2016). Labour market information: An essential part of Canada’s skills agenda. Business Council of Canada. Available here.

Lane, J., & Griffiths, J. (2017). Matchup: A case for pan-Canadian competency frameworks. Canada West Foundation. Available here.

Statistics Canada. (2016). Developing postsecondary education indicators using the education longitudinal linkage platform.

Endnotes

- Statistics Canada is currently providing assistance to six Cree reserves in Quebec in an effort to conduct a labour force survey (LFS) there. In 2010 and 2011, a pilot LFS survey was conducted on the Siksika reserve in Alberta. Statistics Canada is currently transitioning to collecting gender (instead of sex at birth) on its household surveys and also using data integration to fill important data gaps, such as visible minority status on the LFS. Additional questions will be included on the LFS over the next year to gather more information for youth and older workers on the reasons for their employment or unemployment.

- Statistics Canada’s Workplace and Employee Survey (WES), designed to explore a broad range of issues relating to employers and their employees, was discontinued in 2009.

- Until recently, Manitoba purchased oversampling of LFS data to gain insights into Indigenous Manitobans.

- Limitations of the current empirical indicators used to signal shortages and mismatches create confusion and are subject to varying interpretations. A forthcoming edition of LMI Insight will provide additional clarity on the differences in terminology, definitions, and perspectives.