Working Moms

The last UN Progress of the World’s Women, a report that annually takes stock of the situation of women around the globe, focused on families and the role they play in women’s lives. As labour economists (and women) we wanted to take a closer look at a key family decision impacting women’s presence in the job market: having kids. Women’s participation in paid work has always been heavily influenced by the roles we play at home as caregiver, provider and protector. As a brand-new mom, Emna knew the complications of balancing these roles, which affect both her decision to have kids and her decision to return to work.

Baby or No Baby?

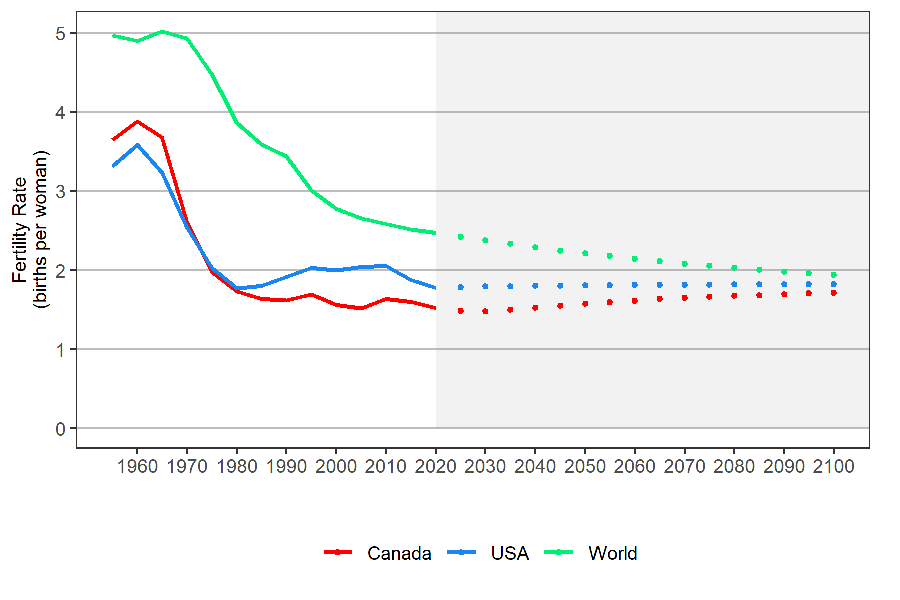

Today, Canadian women have an average of 1.5 children, compared to 2.5 in 1970. This is lower than the global (2.5) and the US (1.8) averages. For the next century, the UN expects fertility rates to converge, with Canada slightly increasing to 1.7 children per woman (see Figure 1). Global fertility rate decline is one of the most noticeable demographic trends of recent decades (from 4.9 in 1970 to 2.5 today).

More than ever, women participate actively in the job market and are free to decide whether or not to have children (and how many). There are some challenges, however.

Low fertility has been accompanied by unfavourable working conditions for women, including loss of education investment and over-representation in non-standard jobs, like part-time and temporary work with no maternity benefits. Some countries, like the United States, do not even meet the 18-week minimum maternity leave recommended by the World Health Organization and UNICEF.

For Emna, getting information about the conditions under which she could pause and resume work — including access to maternity and parental leave — played a role in her decision.

Figure 1. Fertility Rate Estimates and Projections, 1950–2095

Source: World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision, United Nations Population Division.

Smooth Transition

After maternity/parental leave, women are expected to come back to work, revive our skills and resume our roles in the labour market. But returning to work is not a given. After being the main care provider for several months, we still bear the bulk of household work, including organizing activities and juggling medical appointments. This must be done while rediscovering our place at work and working with colleagues who do not face the same hurdles. The decision to return to work is not a trivial one. It must be made without feeling pushed back into work with no support.

Preparing the conditions and smoothing the transition from maternity leave to work is an important issue in retaining moms who are returning to the workplace. For Emna, knowing that she would be able to access affordable childcare was a pre-condition to being able to combine motherhood and a career. Employer programs like flexible hours and working from home can assist further. Moreover, offering such accommodations to both parents can help them better share the parental responsibilities of childcare, school, extra-curriculars, appointments, illness, and so on.

Single Moms

Some mothers face even greater barriers. Families headed by single mothers are high risk for poverty because women earn, on average, less than men do, and the career costs of parenthood fall largely onto women. As one of the most vulnerable groups in the labour market, single moms need more attention in all related policies and programs.

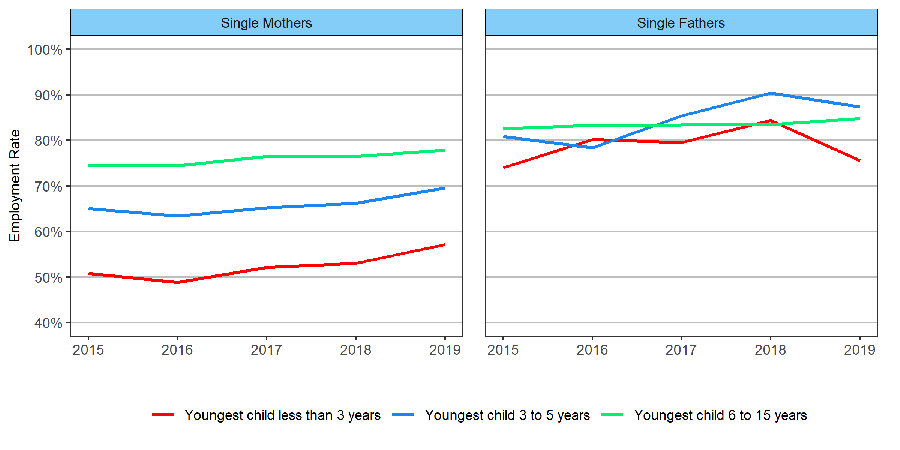

Comparing the employment rates of Canadian single moms and single dads with kids in different age groups illustrates one key issue (Figure 2). Although employment rates for single moms increased over the five years from 2015–2019, they remained below that of single dads. Unsurprisingly, as kids grow older, their single mom’s likelihood of employment increases as well, a pattern not observed for single dads.

Figure 2. Employment rates for single parents in Canada, 2015–2019

Source: Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0120-01

Right Policies, Right Programs

When the time came, Emna had to navigate her desire to have children (and how many) with the career plan she had in mind. Knowing that she’d have access to maternity/parental leave and benefits as well as affordable childcare services was essential.

In a recent LMIC study, we found that women are more likely to look for information about job benefits (including employment insurance and parental benefits) compared to men. But benefits are not enough. When parental leave ends, supportive workplace environments — including flexible working hours and other family-friendly policies — can aid the transition back to work.

By providing more reliable information on benefits and related labour market information before and after maternity, we can help women make the right decisions for them about motherhood and returning to work. LMIC is committed to contributing to more mother-friendly workplace information. Stay tuned!

Behnoush Amery is a Senior Economist with LMIC. Her work currently focuses on labour market information research related to the future of work, the relationship between education and labour market outcomes, as well as the estimation of granular labour data.

behnoush.amery@lmic-cimt.ca

Emna Braham is a Senior Economist with LMIC. She is currently working to assess the state of labour market information in Canada and conducting forward-looking research in collaboration with stakeholders.