Building a Decision-Based Framework to Understand LMI Needs

An Insight Report from the Labour Market Information Council and the Future Skills Centre

July 2021

Foreword

The partnership between FSC and LMIC focuses on the development of new and innovative methods that will enable career development professionals to connect Canadians with timely and relevant labour market information to support informed career and skills-related training decisions. A significant part of our joint work centres on developing a state-of-the-art data repository, and we’re mindful of the need to consider both the quality of the information, as well as how it can best be delivered for uptake and usage.

With this in mind, this latest joint report highlights that the information Canadians need extends well beyond what is usually considered essential data. For labour market information to be relevant and suitable to the diverse needs of Canadians, our work must be centred on the decisions confronting Canadians in a time of immense change and labour market transition.

Our user-centric approach to developing and sharing labour market information is essential to the success of our work. This focus on diverse users will be our guidepost as we equip front-line organizations with best-in-class tools and insights for working alongside Canadians as they navigate their career choices.

Tony Bonen

Director of Research,

Data and Analytics

LMIC-CIMT

Tricia Williams

Director, Research, Evaluation,

and Knowledge Mobilization

Future Skills Centre

Key Findings

- For labour market information (LMI) to be accessible, relevant and suitable for meeting the diverse needs of Canadians, it must consider who is using LMI and what they are using it for.

- Framing LMI appropriately requires a thorough understanding of the decisions that users face, while accounting for an individual’s unique circumstances.

- Building on previous work in this area, LMIC is developing a model to capture, analyze and disseminate LMI that:

Focus

Focuses on decision points associated with life and career transitions to better tailor information to serve a variety of LMI user groups and needs.

Integrate

Integrates the changing nature of work (e.g., automation, ageing workforce) by including disruptive, restarted and progressive career transitions.

Acknowledge

Acknowledges the traditional concept of roles (e.g., parent, student) played by individuals in the decision-making process but expands it to a more inclusive LMI user base (e.g., recent immigrant, person with disabilities).

- This approach is useful in considering how to frame a new partnership between LMIC and the Future Skills Centre that aims to equip front-line organizations with tools and insights needed to help Canadians navigate their career choices. The approach helps to identify transitions that are particularly relevant for the project scope, notably:

Early Career Planning

Early Career Planning transition, characterized by the decision to enter the labour market or explore the option of post-secondary education.

Horizontal Career Transition

Horizontal Career transition, characterized by moving to an adjacent occupation or starting a new career path with current skills and education.

Introduction

Every day, Canadians and the organizations that support them seek labour market information that is difficult to access or that is not sufficiently tailored to meet their individual needs. In the wake of COVID-19, decision-making has become even more difficult and career development practitioners are coping with urgent, escalating client needs. In December 2020, the Future Skills Centre (FSC) and the Labour Market Information Council (LMIC) announced a partnership to address these issues by piloting an open cloud-based data repository to facilitate and streamline access to practical, relevant information. As we begin this pilot project, we are developing a framework to support our data decisions and assist us in collecting, transforming and presenting relevant information.

In 2018, LMIC identified the lack of individually relevant LMI as one of several persistent information gaps in Canada. Next, LMIC surveyed over 20,000 individuals and businesses across ten user groups (e.g., persons with disabilities, current students, recent immigrants, etc.) to better understand the LMI needs of each. We learned that the types of data individuals seek — such as wages and work requirements — are remarkably consistent across these broad user groups and demographic categories. Subsequent analysis with members of each group, however, indicated a wide array of priorities regarding how the information should be transformed, curated and presented in an individually relevant context.

The challenge we now face is to define and identify individuals’ relevant contexts to maximize the potential impact of LMI on their outcomes. In general, the context that makes labour market information — or any information — relevant rests on two key questions. First, who is using the information? The identity of an LMI user will depend, in part, on their demographics, but also their background, personal characteristics and preferences, all of which influence how individuals understand and interact with LMI. Second, what is it being used for? The intended use for LMI will depend on what decisions the person faces and what transitions they navigate.

To deliver LMI that is contextualized to the widest set of audiences, we narrow the scope by focusing on the latter question while maintaining flexibility with respect to the former. To do so, we develop a framework that draws on career development theory. Specifically, we expand Super’s (1980) Life-Span, Life-Space model to incorporate the identity of an LMI user through the roles they play and the job-related decisions they make as they move between life stages. Our framework identifies five key labour market decisions that most individuals encounter as they navigate the world of work and progress in their work and life. In this report we focus on these key decisions points to derive insights into the types and structure of labour market information most relevant to each decision.

Searching for the Right Theory

Having begun in the early twentieth century, career development has evolved into a comprehensive system of theories and intervention strategies aimed at addressing concerns related to career decision making, planning and effectively navigating learning, work and transitions. Historically, many theories of career development have guided its practice, six of which are summarized in Table 1. While each framework has its strengths and limitations, Super’s Life-Space, Life-Span model stands out in that it contains the core elements needed to define and identify LMI users’ relevant contexts.

Table 1: Six core career development theories

| Theory/Approach | Basis | Key Ideas |

|---|---|---|

| Trait Factor Theory | Frank Parson’s (1909) Tripartite Model of vocational direction | Individuals are matched to careers where there is high congruity between their traits (e.g., aptitudes, interests, personal abilities) and the factors of the occupation. |

| Vocational Typology and Personality Theory | John Holland’s (1958) Occupational Themes (RIASEC) | People prefer jobs where they can be around like-minded individuals, use their skills and abilities, and express their attitudes and values. |

| Developmental Theory | Donald Super’s (1980) Life-Span, Life-Space theory | Careers unfold over the life span of an individual. As people pass through different life stages, they take on different roles, which give insight into their values and career goals. |

| Social Cognitive Career Theory | Albert Bandura’s (1986) general social cognitive theory | An individual’s motives and behaviours are based on experience. A person with a positive view of their own abilities will be more successful at achieving their career goals. |

| Constructivist Theory | Peavy (1992) and Savickas (1993 & 1997) | Individuals construct their own meaning from their experiences and have very different perceptions. Personal experiences and principles are emphasized to empower individuals in their approach to their careers. |

| Planned Happenstance Theory | Krumboltz’s (1996) learning theory of career counselling | Unplanned events can lead to good careers. Individuals who are curious, persistent, flexible and optimistic are more likely to succeed given an uncertain and changing job market. |

“Super” Charged

Super’s developmental model is premised on the idea that people’s views of themselves change over time, depending on their experiences and stage in life. It highlights work-related decision making as a developmental process that takes place throughout a person’s “life span” and within their “life space.”

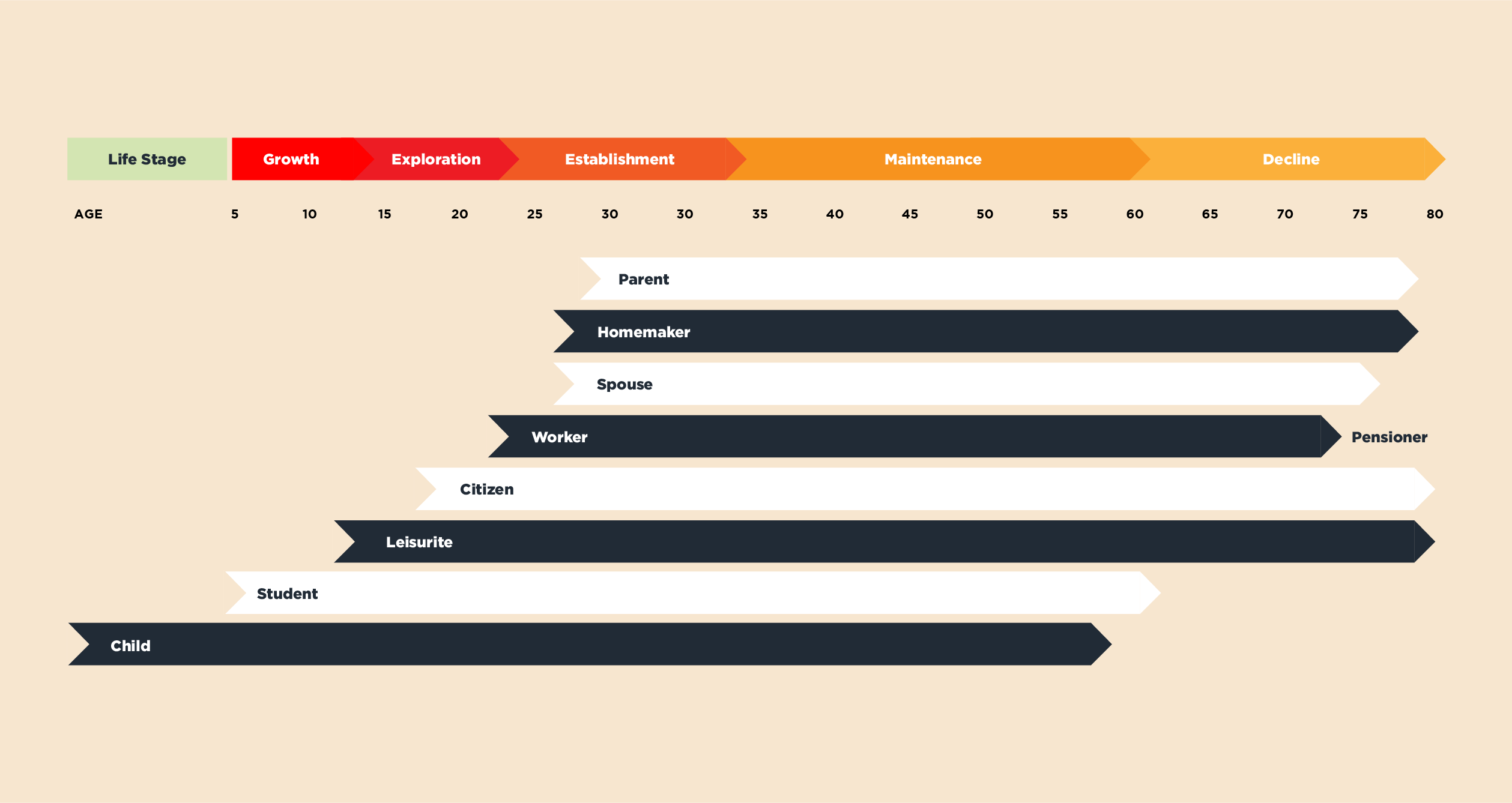

The life span is divided into five “life-cycle” stages through which people progress sequentially as they age: growth, exploration, establishment, maintenance and decline (life stages are illustrated in Figure 1). Each stage consists of several key developmental tasks that an individual is supposed to master before moving forward (see Table 2).

Figure 1: Super’s chart of the life stages and roles

Adapted from Super (1980).

Table 2: Life-cycle stages and career tasks

| Life Stage | Developmental Tasks |

|---|---|

| Growth | Develop interest in one’s vocational future; acquire appropriate attitudes and behaviours toward work |

| Exploration | Narrow occupational choices; form tentative decisions about needs, interests and abilities |

| Establishment | Keep and advance in one’s job; become an organizational citizen |

| Maintenance | Gain new skills to avoid stagnation and remain competitive |

| Decline | Disengage from work; plan for retirement |

The life space is comprised of the places in which we work, live and engage (called theatres) and the roles an individual may play (e.g., child, spouse, parent). Super describes four principal theatres and nine major roles in his model but acknowledges that additional theatres and roles may exist.1 It is important to note that individuals are not expected to enter all theatres or play all roles. Moreover, roles are not restricted to one theatre (although each role is associated with a primary theatre). For example, the roles of child and spouse are primarily played in the home but may be played in the school or workplace. The roles an individual plays are also linked to their life stage. The student role, for instance, is most influential in the early stages of one’s life span, while worker and parent roles typically become important later in life. Thus, while the model communicates a linearity and chronology to the theatres and roles, an individual may play more than one role at a time in more than one theatre.

As people progress through each stage, adopting new roles and discarding others, their concept of self evolves, and with it, their vocational identity and career goals. This process gives rise to a variety of decision points that a person will encounter during their life. Career development is thus modelled as the interaction of multiple factors that occur throughout a person’s life span (i.e. life stage) and life space (i.e., theatre and role).

1 Theatres: the home, the community, the school and the workplace. Roles: child, student, leisurite, citizen, worker, spouse, homemaker, parent and pensioner.

Super 2.0

By specifying career development in terms of stages and roles, Super’s model provides the basic components needed to broadly identify and define an LMI user’s relevant context. However, long-run trends such as rapid technological innovation, demographic shifts and climate change, as well as evolving gender roles and identities have altered labour markets and the decisions surrounding them. As a result, this model no longer offers a complete picture of modern workers and labour markets in Canada and requires updating in order for it to provide an understanding of LMI users’ relevant contexts.

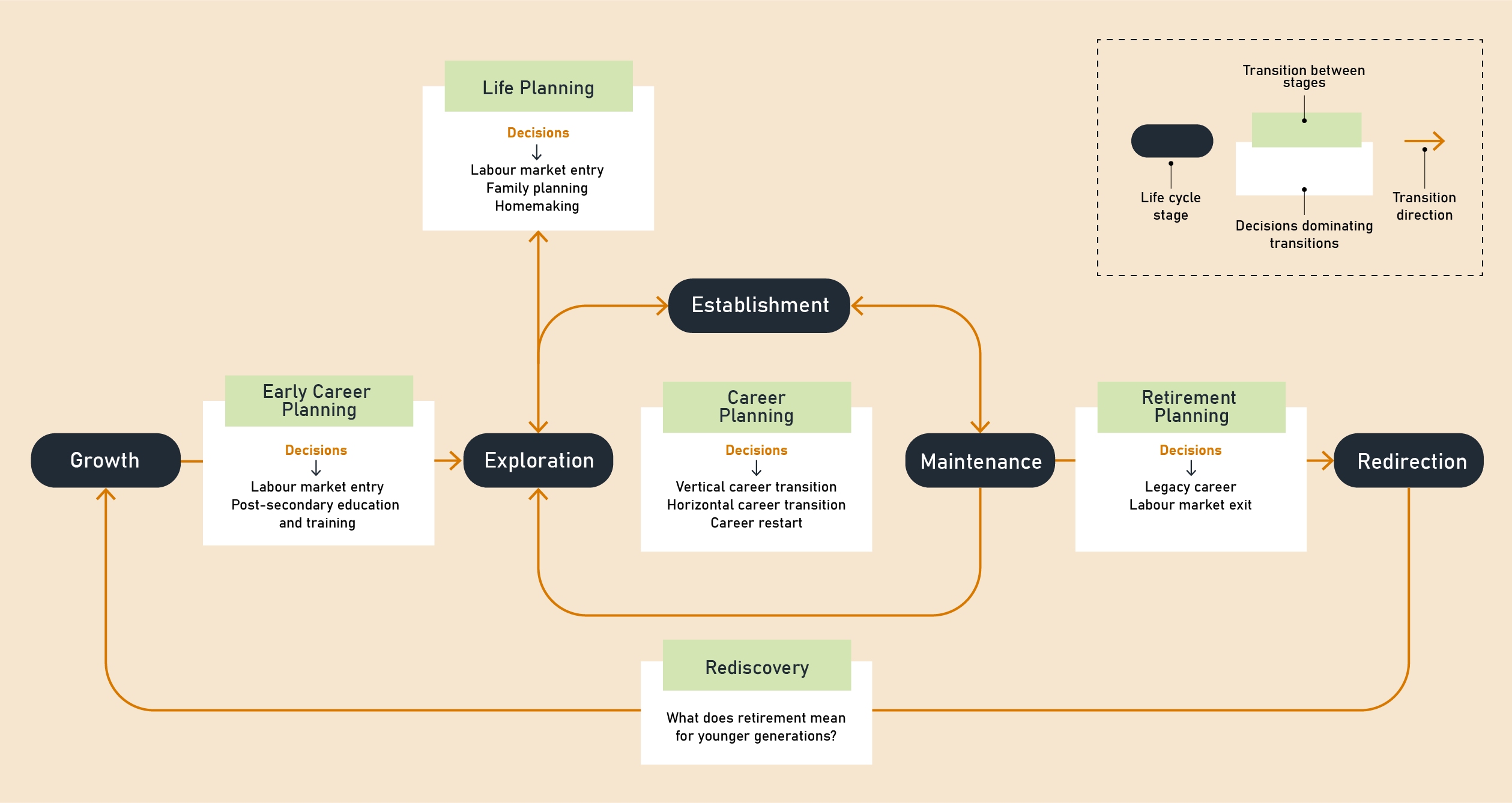

To that end, we propose the following three adaptations to Super’s model: 1) Greater focus on the transitions between life stages to better identify the main decisions driven by these transitions; 2) Allowing for multidirectional career transitions in the framework to account for the changing nature of work; and 3) Expanding the concept of roles beyond traditional concepts (student, parent, worker) to include a wider variety of LMI users.

Focusing on transitions between stages

Super conceptualizes decision points as arising from the transition between roles. We propose, based on the findings of our past surveys of LMI user groups, that transitions between life stages are the key drivers of career-related decision making. As individuals move or consider moving from one stage to the next, they are confronted with a set of key decisions (e.g., moving from exploration to establishment, an individual may search for senior positions in their current organization or elsewhere). Establishing transitions between life stages as the motivation behind decisions allows us to identify and analyze the common decisions experienced as one moves through life.2 It is important to note, however, that people can also face non-transition decisions — those that do not coincide with a transition between two particular life stages. These are often temporary and may be initiated by personal or labour market shocks (see Box 1).

| Box 1: Non-Transition Decisions

The framework outlined above utilizes Super’s career development theory to identify labour market decisions relevant to most Canadians (at least a few times in their lives) while still recognizing the different user identities and their impact on LMI demanded. However, people are also faced with important career decisions independent of any transition between life stages. Such decisions are transitionless; they can happen in any point in life and the change they cause is often temporary, or at least not necessarily life path–altering. Typically, a non-transition decision will be brought about by a personal or economic shock. For example, a sudden illness of a loved one can require important decisions about work arrangements, which nevertheless allow one to continue along the same long-run career and life path. |

2 This is not to say that changing roles do not motivate decisions. Transitions can be brought on by changing roles, as well as changes within a role, such as career progression or changing family circumstances. A person’s education and career pathway can be influenced by internal and external factors as well, such as changing preferences and priorities or labour market disruptions, like COVID-19.

Integrating multidirectionality

The rapid growth of technology, the increase in life expectancy, more frequent career shifts and more diverse definitions of success all challenge the linearity and age dependence of the life stage and role progressions proposed by Super (see Box 2). Therefore, in our framework we break the connection between life stage and age and allow for multidirectional movements between life stages.

| Box 2: It’s a Brave New World

Changes in the labour market resulting from megatrends such as technological growth (e.g., digitalization, automation), demographic shifts (e.g., ageing workforce, immigration) and climate instability (e.g., extreme weather events, other environmental risks) suggest that the future of work will be uncertain, volatile and characterized by job loss as well as job creation. These disruptions will impact labour markets and influence the decisions people will need to make in the future. For one, they underscore the importance of lifelong learning (LLL) — acquiring and updating abilities, knowledge and qualifications throughout life. Workers will have to train and retrain just to maintain relevance, which implies that the “student” role will become increasingly important. Moreover, frequent job changes are increasingly common and telecommuting has been blurring the line between work and home, altering needs and perceptions of success. Six in ten millennials are open to quitting their job for an opportunity elsewhere. However, they are just as loyal to employers if they get what they need — including opportunities to learn, grow and advance, a sense of purpose, and quality management. They are also more willing to accept non-upward career moves. Canadians are also living and working longer than ever before. Suzanne L. Cook (2013) proposes a new life stage called “redirection,” which accounts for workers who take on new opportunities and roles in the world of work after retirement. Similarly, gender roles and identities are evolving. Canadian women still face significant barriers when it comes to work — a finding highlighted by the recent COVID-19 job losses — as do sexual minorities. White (2014) finds that sexual minorities make career decisions to minimize exposure to homophobia and maximize exposure to affirming professional and personal supports. While our framework has been designed to be conscious of the above factors, we recognize that it cannot encompass all the trends of the labour force, its actors and the interactions between them. |

Expanding traditional roles

Transitions between common life stages explain the consistent data needs we identified among LMI users and we believe they are the primary drivers of decisions. However, roles and actor identities are an important secondary dimension that affect transitions, decisions and the concerns and considerations of LMI users in a myriad of ways. For example, immigration can be the cause of a labour market transition (see the example of Alex in Table 3 below). On the other hand, individuals from different user groups can experience the same transitions, yet have different considerations, such as accessibility for a person with a disability considering a mid-career transition. Thus, rather than defining work/family roles as in Super’s model (e.g., student, worker, parent, etc.), our approach allows for a wide array of roles that can overlap, change and intersect. As one example of the expanded set of roles, previous LMIC work targeted nine LMI user groups such as persons with disabilities, recent immigrants and recent post-secondary education graduates. Evidently, a person can identify with each, some or none of these roles. The combination of LMI user groups, Super’s roles and other actor identities provides an additional qualitative dimension to our understanding of LMI needs that will become an integral part of our framework going forward.

The “Super” Duper Decision Grouper

Figure 2 presents our conceptual “Super” duper decision grouper map. The map shows multidirectional transitions between life stages and the most common labour market decisions associated with each transition. The five decision points align with the non-sequential transitions between the five stages in Super’s original model (see Table 1). Each transition point is associated with specific decisions related to the questions an individual is likely to face in that transition. For example, as a person moves from Establishment to Maintenance, they enter the Career Planning transition in which they are likely to make decisions regarding career advancement (i.e. Vertical Career transition). As we utilize multidirectional transitions, one can also move in the opposite direction, from Maintenance to Establishment. This Career Planning transition will focus on decisions around re-establishing oneself in a similar or adjacent field or, in a Horizontal Career transition, a position requiring similar experience.

Figure 2: LMIC’s transitions map

“Legacy Career” is a registered trademark of Challenge Factory. This term is used with their permission.

This conceptual map helps to identify the type of data and the structure (i.e. format, context) of LMI most likely needed by the individuals making transition-related decisions. Table 3 provides a few examples of how the decisions identified in the map can help hone in on the relevant context for the labour market information being sought. For example, a mid-career worker might need to transition into a new industry, or a newcomer to Canada might be looking for work in the most promising field open to them. In each case, similar data are needed — wages, vacancies, skill requirements — but the relevant labour market information will be contextualized in different ways specific to the decision at hand. In the examples in Table 3, Alex and Jack both face the same decision and thus both need skills information, vacancy information and occupational outlooks. However, their different context implies that Jack will want to find occupations with skills similar to his while Alex would focus on finding occupations with the highest growth or demand.

Table 3: Examples of key labour market decisions

| Transition | Decision | Specific Decision | Likely LMI Needs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exploration to Establishment | Labour market entry | Jill is nearing the completion of her bachelor’s degree and is debating taking an entry level job in her field or pursuing a master’s degree. | Earnings information for bachelor’s vs. master’s graduates in her field. |

| Maintenance to Exploration | Career restart | Jack’s job in manufacturing has been automated. He has 15 years of experience and wants to upskill to start a new career. | Skills requirements in growing sectors in his area that are similar to his existing skill set. |

| Alex is a recent immigrant whose industry is inaccessible to him in Canada. He wants to find quick reskilling in a job with many vacancies to maximize his employment prospects. | Job vacancies and expected employment growth in different occupations. Reskilling programs and funding options. | ||

| Non-transition | Changing career scope | Maha is near the end of maternity leave and is not prepared to go back to working 9–5. She needs flexible work arrangements. | Wages for part-time work in her local area. Telecommutable jobs in her field. Childcare. |

It is important to acknowledge another dimension of career decision making not directly addressed in this map: client readiness. In each of the transition points, different individuals may have varying levels of readiness to complete the transition. For example, Jack (Table 3) is in the Career Restart transition and exploring new career options. Someone else in this transition may already know which career they want to pursue and be taking steps to fill in their skills gaps. A common approach used by career development practitioners that addresses this readiness dimension is the Employability Dimensions Framework (see Box 3).

| Box 3: Transitions and Employability Dimensions

Employability Dimensions3 refer to the six major categories of needs, knowledge and skills that support successful employment outcomes:

These dimensions range from ensuring that basic needs are met to build readiness, building self-awareness, developing informed decision-making abilities, identifying skill requirements and the supports to enhance them, learning strategies to successfully find work, to keeping work once it has been found and managing career progression. |

3 The six dimensions as outlined by the CCDF. Copyright CCDF, The Canadian Career Development Foundation 2020 — excerpt from Career Development Process Course.

The Way Forward

Context is crucial to providing labour market information that is accessible, relevant and suitable for meeting the needs of a diverse body of users. Framing LMI appropriately requires a thorough understanding of the decisions that users face, while providing space for an individual’s role to be accounted for. For this purpose, LMIC has drawn from and added to Super’s Life-Space, Life-Span model, which provides a theoretically grounded approach to understanding how different users might use LMI through a set of a key transitions.

This work also raises new questions and challenges. We learned that labour market information needs depend on individual situations, which may call for the creation of a deeper taxonomy of decision contexts and relevant LMI needs. A second challenge, arising from the first, is to consider the circumstances unique to certain groups and how they may affect LMI needs, such as jobs and sectors that are appropriate to and receptive of disability-specific workers, as well as a gender diversity lens on sectors, employers and jobs.

As we move forward in the LMIC–FSC partnership, it will be important to identify and validate the comprehensive set of decisions that different users make at each transition point. This process will be achieved through continued research and consultations with stakeholders, including career development and human resource professionals, among others. In addition, we will identify the best ways to package information to ensure that it is accessible, relevant and suitable for the needs of different users. This work, to be guided by the Career Development Stakeholder Committee, will take place over the coming months.

Acknowledgements

The "Building a Decision-Based Framework to Understand LMI Needs" report is funded by the Government of Canada's Future Skills program.

![]()

The opinions and interpretations in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.