The Pandemic and Emerging Labour Market Information Gaps

LMI Insight Report no. 37

November 2020

Table of Contents

Key Findings

- The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented job losses in Canada and around the world. Although a substantial share of the jobs lost have been recovered, as with all crises, there are often long-term consequences on those most impacted.

- An assessment of these impacts has revealed several important labour market information (LMI) gaps. Filling these gaps would enable us to better understand the distributional impacts and recovery efforts related to the pandemic. These gaps include:

- Systems for transmitting raw administrative data into usable information are slow and out of date for data sources such as CERB, CEWS (or replacements) and EI, which hold the potential to deliver robust, real-time insights. These data also have limited granularity (e.g. socio-demographic characteristics of benefit recipients).

- Understanding the skill requirements of jobs was already identified as a gap prior to the pandemic, but the unprecedented job losses, unevenly distributed across sectors, put renewed emphasis on common standards for identifying and measuring skills. These indicators support job seekers transitioning to new areas of work.

- Systemic and timely insights regarding childcare options and working parents are essential to an efficient, inclusive and successful labour market recovery. Data on childcare services and the labour market characteristics of the parents who require it are limited in their availability and accessibility.

- Students and young Canadians are entering the labour market at its weakest point in the modern era. There is a need for more timely information to help them navigate this altered world of work and support policy makers in their efforts to minimize the long-lasting damage of the pandemic on their labour market outcomes.

- The sector-specific impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted the uneven distribution of underrepresented groups across the economy. Tracking labour market outcomes by demographics such as ethnicity and gender identity will help support the long road to recovery in an inclusive manner.

- To better understand these and other labour market information gaps, Statistics Canada and LMIC will work closely to conduct a targeted survey of stakeholders to validate the gaps, provide insights on additional information needs, and seek input on the labour market information priorities of these stakeholders.

Introduction

The seven months between March and October 2020 recorded the biggest swings in employment on record. Total employment fell by more than three million during the COVID-19–induced economic shutdown in March and April, and average hours worked dropped by 15% over the same period. The subsequent months saw the fastest ever job growth in Canada, with 79% of the jobs lost being recovered by October. Looking ahead, it is unclear how rapidly labour markets can return to their long-run trends — particularly as a second wave of coronavirus infections began as autumn 2020 arrived.

Amid these rapid changes and continuing uncertainty, LMIC launched the Now of Work Annotated Bibliography to track and summarize the latest research, policy and data developments in Canada and around the world. To date, we have reviewed over 120 reports ranging from empirical analyses by Statistics Canada to theoretical papers published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in the United States. The annotated bibliography highlights persistent — as well as new and emerging — labour market information (LMI) gaps in Canada. This LMI Insight Report discusses these gaps. In particular, we try to clarify the gaps identified in the literature to date and chart a path forward to better understand the needs for timely and reliable data specifically for sub-population groups.

This report is divided into two main sections. The first provides an overview of the labour market impacts of the pandemic. The second discusses the various LMI gaps revealed by assessing the impacts of the crisis and research undertaken on the pandemic to date.1

Section 1: Overview of the Labour Market Impacts of COVID-19

What has happened since March 2020?

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely impacted the world of work. As the International Labour Organization (ILO) and many other international organizations and researchers have noted, the impacts have not been limited to job loss — the quality of work and the structure of work have also been deeply affected. The ILO estimated in May that 94% of the world’s workers live in countries with some sort of workplace closures in place. Across the world, governments and international organizations reacted to the pandemic by providing unprecedented support to workers and businesses.2

In Canada, following widespread business closures, the labour market hit bottom in April 2020. About 80% of small businesses reported laying off employees as employment fell by more than three million from February to April. In April, the Canadian labour market, as well as other economies around the world, began to recover.3 Several analyses provided insights for pan-Canadian policy makers to make the most informed decisions possible when determining which sectors to reopen first.4 Despite the quick rebound, a new round of restrictions has been put in place in many parts of the country, which may affect the recovery going forward.

Several sectors were particularly hard hit at the onset of the crisis. The highest job losses took place in the accommodation and food services, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and real estate sectors. Between February and April 2020, the tourism sector — which overlaps with accommodation and food services as well as sales and service occupations — experienced a stunning 42% decline in employment in just two months (LMIC, 2020).5

Canada’s manufacturing sector was also hit hard with a 17% drop in employment between February and April (LMIC, 2020). This drop in manufacturing employment is comparable to the start of the 2008 global financial crisis. However, the manufacturing sector has since seen a decent recovery in employment. Based on a Statistics Canada report, employment growth in the goods-producing sector in August was almost entirely attributable to manufacturing (+1.8%). The Conference Board of Canada also highlighted that the uncertainty of the COVID-19 outbreak will delay investment decisions in different sectors, particularly in the energy sector. Indeed, western provinces have been hit hard by COVID-19 and by structural challenges in the oil and gas sector (LMIC, 2020).6

Conversely, certain sectors were deemed “essential” and kept open throughout the lockdown. In addition to the health sector, many occupations in sales and services (such as grocery stores, gas stations and other basic consumer needs) remained open during the lockdown despite the relatively high risk of exposure to workers. Nevertheless, the sales and services sector faced considerable job losses. In addition, many of these workers lack the financial security to weather extended bouts of unemployment or severely reduced hours. Indeed, sales occupations accounted for many of the two million individuals in Canada employed as casual and contract workers. About 93% of casual workers and 85% of temporary contractors work in the service sector.

Using data from the Labour Force Survey (LFS), Lemieux et al. (2020) show that almost half of all job losses due to the pandemic occurred to workers whose earnings lay in the bottom quartile of wage distribution. Low-income workers are mostly employed in occupations that put them at greater risk of exposure to COVID-19. LMIC found that the lowest earners in clothing stores, traveller accommodations, automobile dealers, and amusement and recreation businesses saw employment decline by over 50% between February and April 2020. Studies also show that women are disproportionately represented among these high-risk occupations, specifically among part-time workers, earning less than 2/3 of the median wage, a common measure for poverty wages. Working women with young children — who were their primary caregivers while working from home during the lockdown — were particularly hard hit.

Statistics Canada also collected data via an online questionnaire from more than 100,000 post-secondary students about how the COVID-19 pandemic was affecting their academic, labour market and financial situations. Most participants reported an academic disruption because of the pandemic and a major impact on their employment plans.

These are just a few highlights of the main impacts of the crisis on the labour market and sub-population groups. Other direct or indirect impacts have not been covered in this report, such as the technology effect,7 or the ability to work from home and its consequences on the quality of work/life.8 In looking more closely at the identified impacts of COVID-19 on the labour market, we uncovered LMI gaps that — if they were closed — could help us address policy concerns raised by these impacts. Next section summarizes these existing LMI gaps.

Section 2: Labour Market Information Gaps

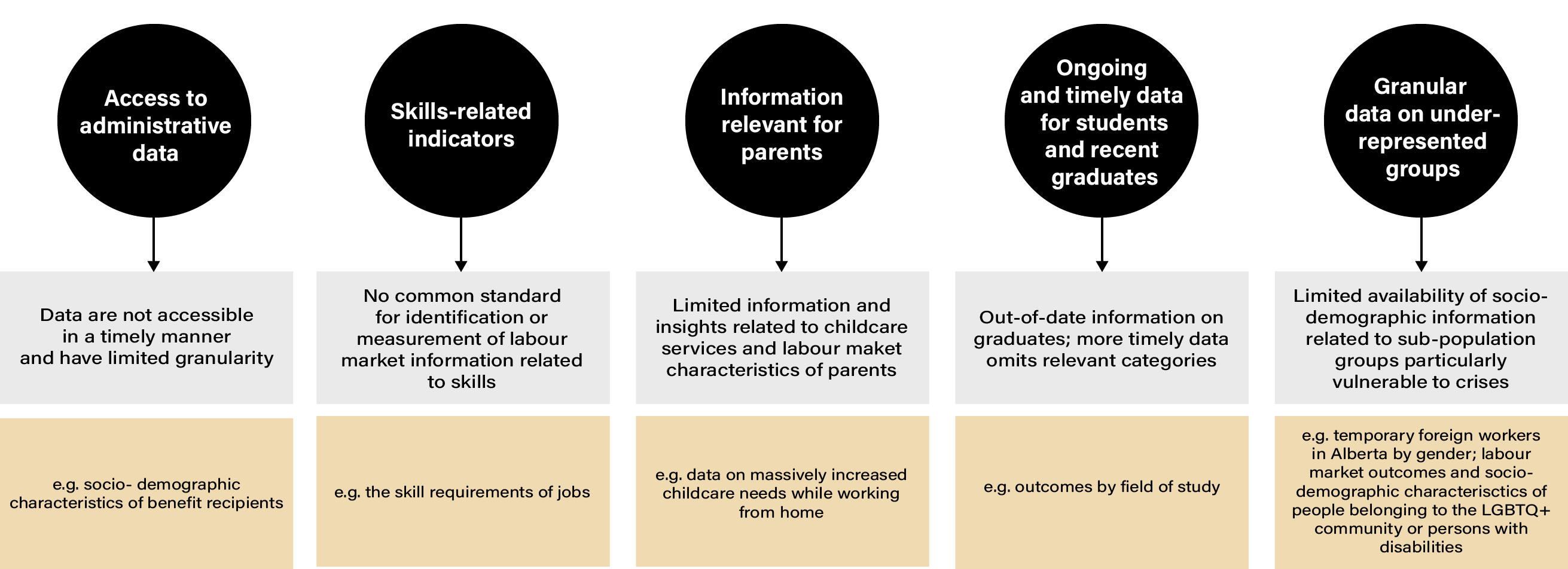

In taking stock of the impacts of the pandemic, our review of related research and analyses revealed both new and persistent LMI gaps. In this section, we discuss these gaps, which all reveal the importance of timely, reliable, accessible data specifically for different demographic groups of LMI users. Table 1 presents our summary of identified LMI needs and gaps.

Table 1: Overview of LMI gaps

Access to administrative data

To address the widespread impacts of the crisis, the federal government introduced a range of new programs for both individuals and businesses. These include the creation of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS). CERB provided financial support ($500 per week) to millions of Canadians who lost their job or whose work hours were reduced because of COVID-19. CEWS provides wage subsidies to eligible businesses.

However, very limited information is available on who received CERB or CEW (or other support programs). For instance, information on occupations or industries that benefited from CERB, previous work experience, or education level of recipients would help in evaluating the effectiveness of the program (e.g. work incentives) and potentially shed light on how to improve program administration.

In general, near real-time administrative data offers robust insights about labour market dynamics. Moreover, timely administrative data can be a key source of that can be leveraged to generate labour market indicators at a more local or granular level than what is available through prevailing survey instruments.

In responding to an emergency like the current pandemic, the policy priority must be on establishing effective support programs rapidly. But designing such programs to include rapid, systematic data strengthens them and any related policy efforts (as well as providing data transparency). Insights from such information can help researchers and policy makers better evaluate program effectiveness.

Indeed, as workers previously covered by CERB have since been transitioned to a modified EI program and other new programs, the need for more accessible, timely administrative data remains essential. This has always been an important information gap in Canada (LMIC, 2019), but the current crisis and new data sources have put renewed emphasis on its importance.

Skills-related indicators

As Section 1 highlighted, during the initial phase of the pandemic, the demand for certain occupations shifted toward those deemed “essential services.” From February to March 2020, for example, the labour market experienced a spike in the demand for security guards, home support workers and store shelf stockers (LMIC, 2020), which necessarily increased the need for workers possessing the unique skill requirements to successfully fill these roles. In addition, the pandemic has accelerated structural shifts in the economy and, along with it, changes in skills requirements. Preparing for the “future of work” has gone from a distant hypothetical to a very immediate priority. In fact, businesses are already reimagining their current business models to facilitate the rapid adoption of more flexible work arrangements. It is also expected that the pandemic will increase the rate of automation.

These changes have put renewed emphasis on the importance of developing robust skills indicators to support job seekers’ transition to new areas of work or re-skilling as the requirements of their current jobs evolve. While progress is being made to identify the skills requirements of occupations in Canada, work in this area is nascent as there is no common standard for reliable skills-related insights. It is essential, therefore, to establish a common understanding of skills and other work requirements and to develop a common set of indicators that will measure them — a need accelerated by the recent employment dynamics and rapid shifts in jobs and work requirements.

Information relevant for parents

Unequal distribution of childcare duties and society’s gendered expectations around childcare have led to greater employment and work–life impacts on mothers than on fathers. This unequal impact continues through the recovery: working women with young children are not returning to their pre-shutdown level of hours worked as quickly as their male counterparts, Canadians with older children, or those without children (Schirle & Skuterud, 2020). This pattern is observed elsewhere, and the employment loss experienced by working mothers, especially single mothers, is likely to have persistent impacts on their earnings potential beyond the crisis. What became clear in the pandemic is the extent to which Canada lacks accessible data on childcare availability and more generally on working/non-working parents.9

Looking ahead, it is likely that work and family life will be increasingly blurred as telework becomes more common. In the new work structure, available and accessible data on the labour market challenges of parents who require childcare services will help policy makers ensure that the recovery in employment is equitable and inclusive.

Ongoing, timely data for students and recent graduates

Young people (aged 18–24) and new graduates are facing multiple shocks from the COVID‑19 pandemic,10 which could lead to the emergence of a “lockdown generation.” The long-run consequences could be severe and could include prolonged underemployment, among other challenges. To understand these implications, Statistics Canada estimated five-year potential earnings losses under different scenarios of youth unemployment rates. Statistics Canada (2020) also collected crowdsourcing data on post-secondary students during the first months of the pandemic. Although crowdsourced data allows for the rapid collection of information on a relevant and timely topic, student-related insights are needed on an ongoing basis.11

The recently launched Education and Labour Market Longitudinal Platform (ELMLP) (LMIC/EPRI, 2019)— which connects annual student outcome data from post-secondary studies and apprenticeships to yearly tax returns — is an important step in this regard. However, these data come with a considerable time lag and lack many key variables (e.g., occupation).

The rapid response by Statistics Canada to collect data on post-secondary students via crowdsourcing, which should be applauded, filled a key data gap on the lack of information on recent graduates’ labour market outcomes during the pandemic. However, given that the effects of downturns for youth more broadly, especially the current cohort of students, is likely to linger with potentially harmful long-run consequences, these efforts must be bolstered to ensure that we can monitor ongoing developments. This will enable us to provide insights on possible short-term and long-term support systems (e.g., training, mentorship) that may be needed.

Granular data on underrepresented groups

Section 1 highlighted the industry-specific impacts of the pandemic and the uneven distribution of underrepresented workers across sectors, as well as their overrepresentation in lower paying occupations. To evaluate the effects of the pandemic on various demographic groups, it is essential to collect and analyze more granular LMI for each group separately. LMI is available for some specific demographic groups (e.g., ethnicity, gender), but it lacks granularity (e.g., the occupations they hold). As such, targeted policies require more refined categories of information to better understand the consequences of the crisis on these groups.

For instance, in collecting crowdsourced data on visible minorities, Statistics Canada found higher shares of strong or moderate income losses compared to white respondents. Recent data from the LFS also provide a good amount of information about immigrants. These show that the sales and services sector, which has been severely affected by the crisis, employs a disproportionate share of immigrants. LMIC found that these workers have lost employment at nearly twice the rate of their Canadian-born counterparts, with female immigrants suffering the worst job losses and the slowest recovery since April.

Other Statistics Canada reports use the LFS to discover the ability of Indigenous people and gig workers to meet their financial obligations during the pandemic.12 However, persons with disabilities, the LGBTQ+ population and temporary foreign workers (TFW) are some of the specific groups disproportionately affected by the pandemic, but there are limited or no data available for these groups.

Although the LFS supplementary questions and data collected through crowdsourcing are available for evaluating the labour market effect on some underrepresented groups, it is critical to collect such information, including more refined demographic categories, more systemically. This would enable more detailed analysis, which in turn could help in the design of more inclusive support systems.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented job losses in Canada and around the world. Although a substantial share of the jobs lost were recovered, full recovery is still far away. Importantly, even as many jobs have returned, there have been significant distributional effects on those who have lost and gained employment. Indeed, as with all crises, there are often long-term consequences on those most heavily impacted. Many will continue to struggle until we have a more complete return to normal for all sub-population groups — whatever that may look like in a post-COVID-19 labour market.

The crisis, however, also provides us with an opportunity to address several shortcomings in the provision of labour market information. Doing so, we will support policy efforts to ensure a sustained and inclusive recovery and prepare us better for future shocks. In this report, we summarized the LMI gaps identified through our Now of Work Annotated Bibliography, summarizing real-time reports in Canada and the world. We noted the following:

- Administrative data are not accessible in a timely manner and have limited granularity (e.g. socio-demographic characteristics of benefit recipients of CERB or newly announced programs to replace CERB, etc.)

- There is no common standard for identifying or measuring labour market information related to skills (e.g. the skills requirements of jobs)

- Limited information and insights related to childcare services and labour market characteristics of parents are available (e.g. data on massively increased childcare needs while working from home)

- Prevailing information on graduates are out of date; more timely data omits relevant categories (e.g., outcomes by field of study)

- Socio-demographic information related to sub-populations particularly vulnerable to crises is limited in availability (e.g., temporary foreign workers in Alberta by gender; labour market outcomes and socio-demographic characteristics of people belong to the LGBTQ+ community or persons with disabilities).

In the coming months, LMIC and Statistics Canada will collaborate to undertake a targeted survey of stakeholders aimed at validating these gaps, providing insights on additional gaps and seeking input on the labour market information priorities of these stakeholders. Jointly with Statistics Canada, we will then report our findings and chart a path forward to closing the information gaps identified.

Acknowledgments

This LMI Insight Report was prepared by Behnoush Amery of LMIC with the support of Zoe Rosenbaum, Anthony Mantione, Brittany Feor, Bolanle Alake-Apata and Kevin Saade. We thank David Ticoll (Distinguished Fellow, Innovation Policy Lab, Munk School, University of Toronto), Ron Samson (Magnet), Ruth Wittenberg (President, BC Association of Institutes & Universities), Vincent Dale and Marc Frenette (Statistics Canada), Kelly Hoey (Halton Industry Education Council), Editha Alido and Lori Zaparniuk (Alberta Labour and Immigration), Asa Motha-Pollock (MaRS Discovery District), Derrick Barrett (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador) and David Chaundy (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council) for their feedback. For more information about this report or our Now of Work Annotated Bibliography, please contact Behnoush Amery, Senior Economist, at behnoush.amery@lmic-cimt.ca, or Tony Bonen, Director of Research, Data and Analytics, at tony.bonen@lmic-cimt.ca.

End Notes

- A full list of the 44 reports used in this research is provided in the reference section, although not all are explicitly cited in this LMI Insight Report.

- The European Commission, for example, assisted EU members in preventing unemployment from skyrocketing through a variety of new funding programs, such as the European Social Fund and a new Coronavirus Response Investment Initiative (CRII). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) also tracked the major economic responses taken by 193 countries to reduce the human and economic toll of the pandemic. Similarly, in a “living paper,” the World Bank and the ILO have documented the social protection measures either planned or implemented by governments across the globe to mitigate the consequences of COVID-19.

- Export Development Canada (EDC) conducted an online survey in May and found that 40% of respondents (businesses) had fully reopened and 43% had partially reopened.

- For instance, the MaRS Discovery District and the Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship mapped the occupational risks based on workplace exposure to illness and physical proximity to people. Their analyses followed the McKinsey study (2020, April 6) for occupations in the United States and a similar exercise in the UK. In addition, the Vancouver School of Economics (VSE) and LMIC jointly created the Employment and COVID-19 Transmission Risks dashboard, which compares the risks and benefits of re-opening different sectors in Canada. Initially, the VSE created the COVID Risk/Reward Assessment Tool of the British Columbia economy (over 300 occupations in over 100 industries). The tool features an interactive figure and a table with more detailed information on the risks associated with specific sectors and occupations. The analysis of risk in the VSE tool is presented according to job description detail, economic factors detail, and risks associated with factors outside of the workplace (household detail).

- Globally, these sectors comprise almost 38% of the workforce. Geographically, this has meant that regions with a greater economic dependency on tourism and hospitality have also suffered greater retrenchment than those relying more on agriculture or professional services. Under its optimistic scenario, a United Nations’ report from July 1 estimated global losses in the tourism sector to be US$1.17 trillion USD, representing nearly 1.5% of global GDP.

- In addition to being affected by COVID-19 protocols, oil prices plummeted in March due to a price war and global demand for energy has remained subdued ever since, thereby limiting the sector’s ability to return to regular operations.

- There is also an overlap between workers who are vulnerable in the current downturn and those whose jobs are susceptible to automation in the future (McKinsey, 2020, April 29).

- It is estimated that most of the jobs that could be performed at home were in the finance, corporate management, professional and scientific industries (Dingel & Neiman, 2020, and Brynjolfsson et al., 2020). On the other hand, in some occupations, such as those in the agriculture, hospitality or retail sectors, either the possibility of working remotely is unlikely or workers have a high degree of physical proximity in the workplace. These workers tend, on average, to be less educated, to be over-represented among low-skilled occupations, to earn lower incomes, and to experience larger job losses than those whose occupations can be done remotely (Mongey, Pilossoph, & Weinberg, 2020).

- A supplementary question was added to the Labour Force Survey’s (LFS) during the pandemic, data for which are only available through Statistics Canada’s research data centres (RDCs).

- Angus Reid Institute (2020, March 25), Lemieux, Milligan, Schirle, and Skuterud (2020, June), and Beland, Brodeur, Mikola, and Wright (2020, May) also find similarly that youth are severely affected by this pandemic.

- Note that the crowdsourced data is not representative of all post-secondary students in Canada.

- Statistics Canada finds that the impact of COVID-19 on gig workers is likely to be unevenly distributed, largely depending on the nature and type of work. Immediate effects will depend on characteristics such as age, place of residence and industry of work. Younger gig workers are more likely to be affected than older ones, who may have diverse sources of income (e.g., pension).

References

Aaronson, S., & Alba, F. (2002, April 15). The unemployment impacts of COVID-19: Lessons from the Great Recession. New York, NY: Brookings.

Agopsowicz, A. (2020, March 20). COVID-19’s threat to Canada’s vulnerable workers. Montreal, QC/Toronto, ON: Royal Bank of Canada.

Alon, T. M., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. NBER Working Paper 26947. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Amarasinghe, U., Motha-Pollock, A., Felder, M., & Oschinski, M. (2020, April 17). COVID-19 and Ontario’s sales and service workers: Who is most vulnerable? Toronto, ON: MaRS Discovery District.

Arriagada, P., Frank, K., Hahmann, T., & Hou, F. (2020, July 14). Economic impact of COVID-19 among Indigenous people. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Government of Canada.

Baker McKenzie. (2020, April 8). Beyond COVID-19: Supply chain resilience holds key to recovery. Oxford, UK: Oxford Economics.

Brynjolfsson, E., Horton, J. J., Ozimek, A., Rock, D., Sharma, G., & TuYe, H. Y. (2020). COVID-19 and remote work: An early look at US data. NBER Working Paper 27344. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

DiCapua, A., Topping, J., & Tapp, S. (2020, July 14). EDC COVID-19 impact survey suggests the worst is behind us. Ottawa, ON: Export Development Canada (EDC).

Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020, April). How many jobs can be done at home? NBER Working Paper 26948. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

EDC. (2020, April). COVID-19 crisis: Challenges mount for many Canadian sectors. Ottawa, ON: Export Development Canada.

European Commission. (2020, March 13). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Central Bank, the European Investment Bank and the Eurogroup: Coordinated economic response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Brussels, Belgium.

Finnie, R., Miyairi, M., Dubois, M., Bonen, T., & Amery, B. (2019). How much do they make? New evidence on the early career earnings of Canadian post-secondary education graduates by credential and field of study. Ottawa, ON: Education Policy Research Initiative and Labour Market Information Council.

Frenette, M., Messacar, D., & Handler, T. (2020, July 28). To what extent might COVID-19 affect the earnings of the class of 2020? StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., & Orton, I. (2020, July 10). Social protection and jobs responses to COVID-19: A real-time review of country measures. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33635

Gopinath, G. (2020, March 18). Limiting the economic fallout of the coronavirus with large targeted policies. In R. Baldwin & B. Weder di Mauro (Eds.), Mitigating the COVID economic crisis: Act fast and do whatever it takes (pp. 41–47). London, UK: CEPR Press (Centre for Economic Policy Research).

Hou, F., Frank, K., & Schimmele, C. (2020, July 6). Economic impact of COVID-19 among visible minority groups. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Government of Canada.

ILO. (2020, March 19). COVID-19 and world of work: Impact and policy responses. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization.

ILO. (2020, April 29). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work, 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization.

ILO. (2020, May 27). ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the world of work, 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization.

IMF. (2020, April 17). Policy responses to COVID-19. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Jeon, S.-H., & Ostrovsky, Y. (2020, May 20). The impact of COVID-19 on the gig economy: Short- and long-term concerns. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Catalogue no. 45280001. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada, Government of Canada.

Kikuchi, L., & Khurana, I. (2020, March 24), The jobs at risk index (JARI): Which occupations expose workers to COVID-19 most? London, UK: Autonomy.

Lemieux, T., Milligan, K., Schirle, T., & Skuterud, M. (2020, June). Initial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Canadian labour market. Spring–Summer 2020, Working Paper 26. Waterloo, ON: Canadian Labour Economics Forum.

LMIC. (2019, July). Search for the LMI grail: Local, granular, frequent, and timely data. LMI Insight Report no. 15. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, April). Making informed choices in an uncertain and changing job market. LMI Insight Report no. 29. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, May). Sectors at risk: The impact of COVID-19 on the Canadian tourism industry. LMI Insight Report no. 30. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, May 8). COVID-19 job losses concentrated among the lowest earners. LMIC Blog. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, June). Sectors at risk: The impact of COVID-19 on the Canadian oil and gas sector. LMI Insight Report no. 33. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, June 5). Job loss impacts of COVID-19 by education, gender and age. LMIC Blog. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, June 18). Impacts of COVID-19 on women working part-time. LMIC Blog. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, July). Sectors at risk: The impact of COVID-19 on Canadian manufacturing. LMI Insight Report no. 34. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, August 6). Canadian immigrants and COVID-19 employment impacts. LMIC Blog. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

LMIC. (2020, September 1). Immigrant employment in sectors most affected by COVID-19. LMIC Blog. Ottawa, ON: Labour Market Information Council.

McKinsey & Company. (2020, April 6). How to restart national economies during the coronavirus crisis. New York, NY: McKinsey & Company.

McKinsey & Company. (2020, April 29). COVID-19 and jobs: Monitoring the US impact on people and places. New York, NY: McKinsey & Company.

Mongey, S., Pilossoph, L., & Weinberg, A. (2020, May). Which workers bear the burden of social distancing policies? NBER Working Paper 27085. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Schirle, T., & Skuterud, M. (2020, July 15). The moms are not all right. C. D. Howe Intelligence Memos.

Statistics Canada. (2020, May 11). Impact of COVID-19 on small businesses in Canada. StatCan COVID-19: Data to Insights for a Better Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2020, May 12). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on postsecondary students. The Daily. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada.

Statistics Canada. (2020, August). Labour force survey, August 2020. The Daily. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada.

Stewart, M. (2020, March 17). Canadian outlook summary: Spring 2020. Ottawa, ON: Conference Board of Canada.

St-Denis, X. (2020, May 18). Sociodemographic determinants of occupational risks of exposure to COVID-19 in Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto.

United Nations. (2020, July 1). COVID-19 and tourism: Assessing the economic consequences. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

VSE. (2020, May 14). VSE COVID-19 risk/reward assessment tool. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, Vancouver School of Economics.

Vu, V., & Malli, N. (2020, April 3). Anything but static: Risks of COVID-19 to workers in Canada. Toronto, ON: Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship.